Let’s talk

.jpg)

Last November, the European Commission published its proposed amendments to the EU’s transparency framework for financial products integrating environmental or social aims, known as the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR).

The goal of “SFDR 2.0” is to honour SFDR’s original intent: to help the EU financial sector allocate capital for Europe’s sustainable priorities.

For market participants, it also aims to reduce the administrative burden, focusing compliance efforts on validating the quality and impact of offered financial products. The proposal also includes a direct answer to the 72% of stakeholders who demanded a specific category for "products with a transition focus" (European Commission, 2023).

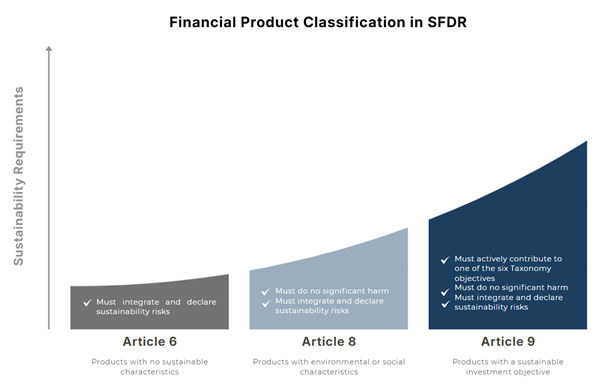

1. SFDR was updated: November 20th, 2025. The original regulation was designed as a transparency tool – and featured 3 categoric labels for funds to disclose sustainable features.

2. Why was it updated?: The market treated it as a marketing menu. Distributors and clients viewed Article 8 and 9 as quality badges, not disclosure buckets.

3. The main problem: A massive, diluted category called "Article 8" that covered everything from dark green impact funds to generic trackers, rendering the label meaningless.

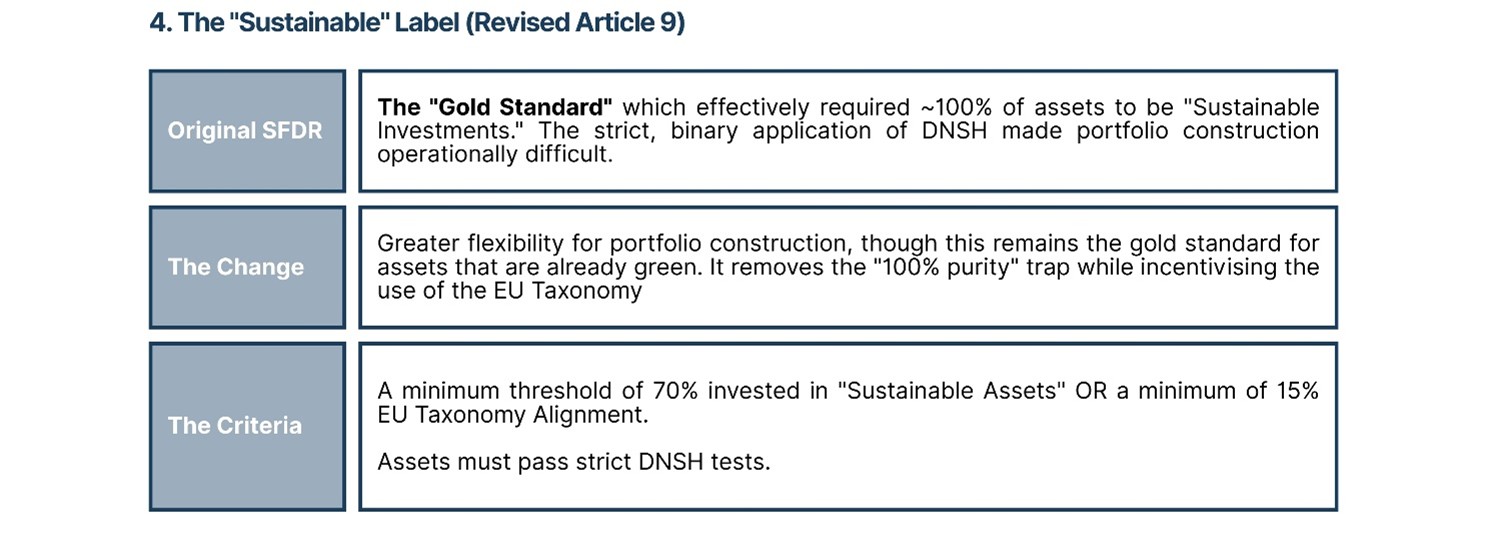

4. The suggested solution (SFDR 2.0): The new update abandons "self-disclosure" for "product eligibility." You can no longer just say you are green; you must meet specific criteria (like a 70% of assets threshold) to use the label.

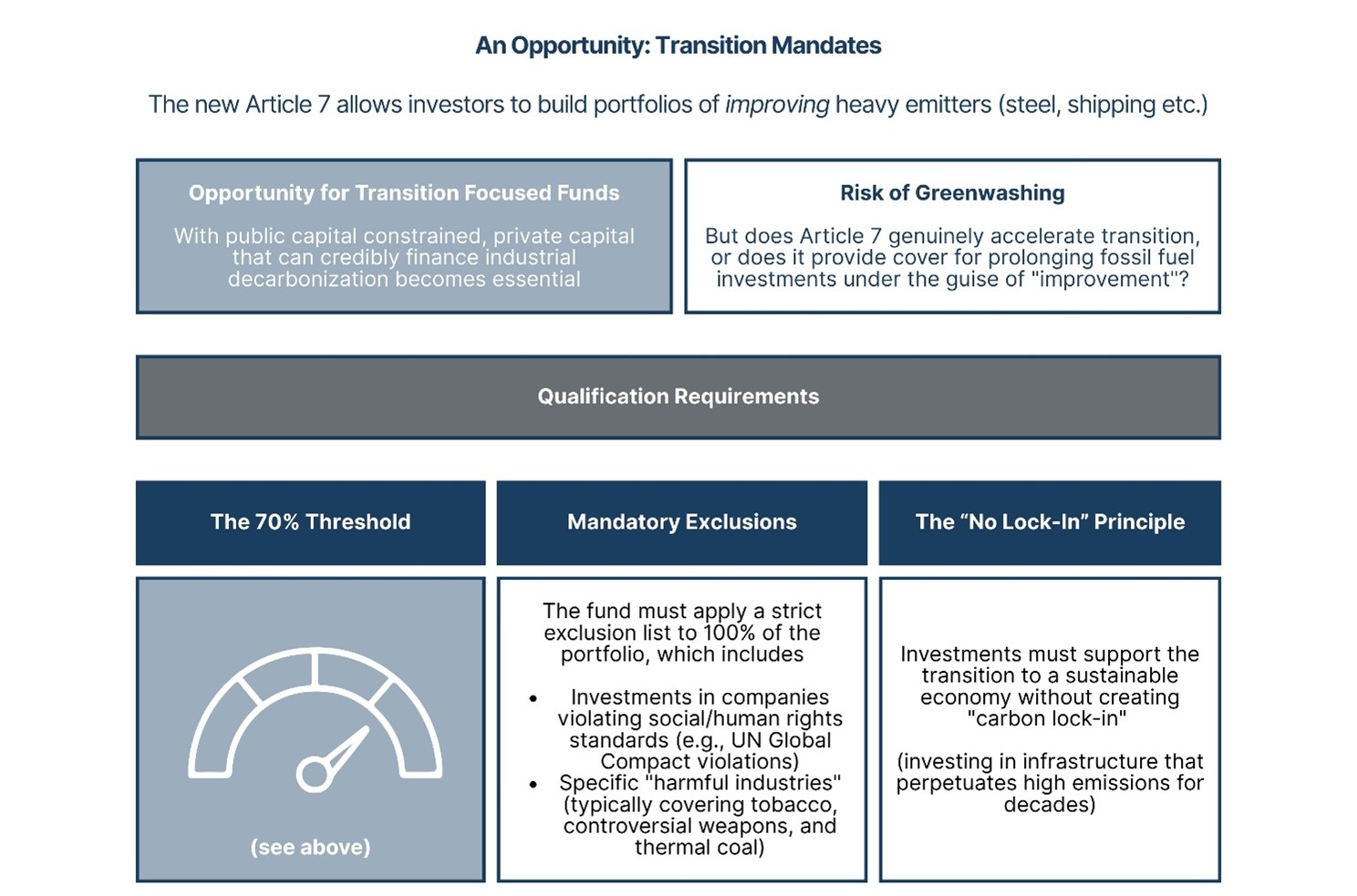

5. The new opportunity: A new, regulated home for Transition Finance - allowing managers to finally fund the "brown-to-green" journey without fear of greenwashing.

SFDR was designed as a transparency tool, setting out how financial market participants had to disclose sustainability information. The framework sought to help investors “who wanted to put their money into companies and projects supporting sustainability objectives, to make informed choices” (European Commission, 2025).

But the market didn't use it that way. Instead, distributors and clients adopted its three distinct Articles as de facto product labels. The result included a massive category called "Article 8" that lost much of its value as a tool for distinction.

i. Definition: Strategies that integrate Sustainability Risks but do not promote specific environmental or social characteristics.

ii. Market Reality: These are standard investment funds. They account for financial materiality (e.g., "how will climate regulation impact this asset's value?") but do not seek positive sustainability outcomes.

i. Definition: Strategies that "promote" environmental or social characteristics alongside financial objectives.

ii. Market Reality: This became the industry's "catch-all" category. It currently encompasses a vast spectrum of products, from passive trackers with basic exclusion lists (e.g., no controversial weapons) to high-conviction ESG strategies. This lack of definition is precisely what led to the "greenwashing lite" concerns SFDR 2.0 aims to solve.

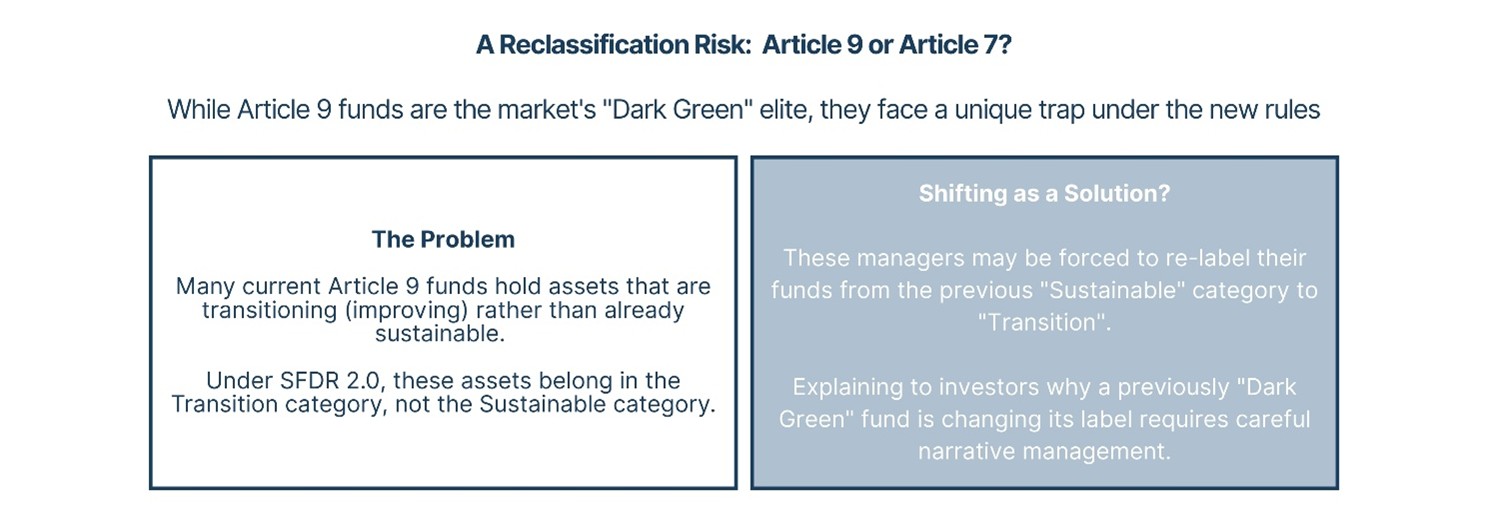

i. Definition: Strategies with a specific sustainable investment objective (e.g., a renewable energy impact fund).

ii. Market Reality: The "Gold Standard." These funds must adhere to strict "Do No Significant Harm" (DNSH) principles for every asset. The operational burden of proving this for 100% of the portfolio proved restrictive, often rendering genuine transition strategies ineligible.

The Commission's own review confirmed what compliance teams have known for years: the previous regime was flawed. 83% of respondents admitted that SFDR was being treated as a "labelling and marketing tool" rather than the disclosure framework it was intended to be (European Commission, 2023).

Almost any fund could claim Article 8 status by adding a few exclusion criteria (no tobacco, no controversial weapons) while changing very little about the portfolio itself. This created a "light green" wash over the entire European market.

79% of industry participants reported that the old rules created "legal uncertainty," while 81% warned that the framework’s limitations were actively creating "risks of greenwashing and mis-selling" rather than preventing them. As noted in the summary of responses, "limitations such as lack of legal clarity... and issues linked to data availability" had fundamentally "hindered the effectiveness" of the regulation (European Commission, 2023).

Additionally, genuine transition strategies (i.e. funds buying dirty companies to clean them up) were homeless. They were too "brown" for Article 9 (which required assets to be already green) but too ambitious for a generic Article 8.

The Commission’s Impact Assessment explicitly calls out this failure. It notes that the old framework failed to channel capital effectively because investors couldn't trust the labels. SFDR 2.0 is the correction: it stops pretending this is just about disclosure and admits that investors need clear, regulated product categories.

The original classification system (Articles 6, 8, 9) is effectively being replaced by three distinct product categories. To qualify, funds must now meet mandatory minimum criteria, including specific asset thresholds. The rules are proposed to go livefrom January 1, 2028. Fund managers have roughly 24 months to prepare, but the strategic decisions start now.

The most dangerous place to be right now is in denial about Article 8 suitability. According to Morningstar Sustainalytics, Article 8 funds make up the majority of labelled funds and could drop from 48% to as low as 22% of EU funds under stricter interpretation. The lack of "grandfathering" means every fund you currently manage must be re-assessed.

On the other hand, for funds with an explicit transition strategy, this marks a new opportunity for distinction.

We now enter the "trilogue" phase: SFDR 2.0 is still just a proposal. The results of political negotiation between the European Commission, the Parliament, and the Council of Member States will determine the real fine print and future of SFDR.

The proposal specifies that the new rules will apply 18 months after the amending legislation enters into force, with a proposed 'start-up period from 2027 to 2028.' The precise timing depends on how quickly Parliament and Council negotiate the text through the ordinary legislative procedure.

i. Who: The European Parliament and Council

ii. What: Details debated over the most controversial elements (e.g., should the Transition threshold be 60% or 70%? Should "Social" funds have their own category?).

iii. Output: A final political agreement (Level 1 text) is likely by late 2026 or early 2027.

i. Who: European Supervisory Authorities (ESMA, etc.)

ii. What: Draft of the "Level 2" Regulatory Technical Standards (RTS)

iii. Output: Submission templates, data fields, and calculation methodologies.

i. Who: Market Participants

ii. What: The full rules are expected to apply from this date.

iii. Output: There is no "grandfathering" for existing funds. This means your entire back book of Article 8 and 9 funds must be re-classified and re-documented by this deadline.

Fund Managers have an 18-30 month runway if delayed. Use 2026 for strategy and 2027 for execution.

This is another amongst several revisions of environmental legislation in 2025. These changes to SFDR represent an attempt at clarity, but the fundamental problem is unchanged: it remains easier to meet technical thresholds than to demonstrate genuine sustainability integration. Bodies like Eurosif warn that the 'ESG Basic'(~ Article 8) criteria may still leave room for greenwashing - we also hope to see robust criteria embedded as the proposal develop.

Our strongest critique of SFDR 2.0 is the same for SFDR 1.0: its "Carbon Tunnel Vision."

SFDR 1.0 effectively created a two-tier system where 'Sustainable' became synonymous with 'Low Carbon'. SFDR 2.0 reinforces this system in several ways:

i. The "Sustainable" label (Article 9) remains out of reach for many nature funds due to the "Data Gap." Proving that a biodiversity asset does "No Significant Harm" requires granular, location-specific data, forcing nature strategies to meet a consequently stricter evidence threshold.

ii. By designing the new 'Transition' category around the same linear, carbon-centric metrics (e.g. GHG intensity), SFDR 2.0 risks repeating this mistake leaving Nature strategies structurally homeless.

iii. Scrapping entity-wide PAI, while intended to reduce administrative burden, creates a dangerous transparency blackout for nature. Nature-related impacts, like water usage, hazardous waste, or deforestation, are often material at the systemic level. By removing the requirement for managers to disclose these impacts at the firm level, investors are left "in the dark" about a manager's total biodiversity footprint. \

Over time, as SFDR has matured, generic Article 6 funds have become the main receiver of fund flows, despite accounting for only 41% of EU fund assets. This has worsened over 2025, with Article 6 funds attracting nearly double the inflows of ESG funds in Q3 (€134bn vs €68bn). The dramatic shift toward Article 6 funds suggests investors are either losing confidence in the ability of sustainability labels to distinguish genuine integration from greenwashing - or abandoning sustainability priorities altogether. Either way, the current system is failing to channel capital toward genuine impact.

One element of SFDR 2.0 that could help rebuild investor confidence is the new Article 7 (Transition) category - provided the right guardrails are in place. A dedicated space for funds that finance industrial decarbonisation in high-emitting sectors does not exist. But is it needed? The design comes with its own risk: if the criteria for a "credible transition plan" are defined too loosely, Article 7 could end up legitimising both the best and the worst of transition strategies.

Even though Article 7 requires transition objectives and plans, the strength of the regime will ultimately depend on how strictly supervisors enforce time-bound targets, interim milestones, and evidence of delivery. If these expectations are weak in practice, Article 7 becomes another part of the problem with transition: legitimised delay and continued access to finance.

For managers who can credibly demonstrate intent and impact, whether through transition pathways with binding targets or nature-positive investment, the changes introduced by SFDR 2.0 raise the bar for entry and simplify ongoing disclosure.

We see plenty of upside for managers “in-the-middle” who are willing to build differentiated capabilities that both investors and regulators can trust.